For decades, the line between commerce and culture has blurred, but a new movement wants to draw that boundary again. The term discommercified captures a rising countercurrent to the hyper-commercialization of creativity. It’s more than just rejecting ads or merchandise—it’s about reclaiming spaces, ideas, and identities from monetization. As defined in discommercified, it’s a push to decenter profit from places where it doesn’t belong, from music scenes to online activism.

What It Means to Be Discommercified

At its core, being discommercified is about resisting the pressure to package, sponsor, or monetize every expression or interaction. It’s pushing back against the idea that value must be measured in revenue or reach. Whether you’re an artist, organizer, or casual participant in a subculture, chances are you’ve felt that subtle pull: Can this go viral? Can it scale? Can we sell it?

Discommercification challenges that mindset. It values things like authenticity, agency, and non-commercial relationships. It asks: What does this look like if we don’t put a price on it? In practice, that can mean a music collective choosing to stream their work on their own terms instead of going through major platforms, or a community forum that declines corporate sponsorship even if it means slower growth.

But it’s not just about refusing money. It’s about redefining how value is created and exchanged.

The Rise of Hypercommercial Contexts

Social media, e-commerce, and influencer economies have made it increasingly normal to treat every aspect of life as marketable content. The promise was more opportunity and access. In reality, this shift often siphons value away from creators and communities toward centralized platforms and corporations.

Even causes once rooted in collective struggle get warped. A protest becomes a photo opportunity. A slogan morphs into a t-shirt line. And behind it all, commercial interests scap onto authentic expression, turning it into aesthetic or lifestyle branding.

Discommercified spaces offer alternatives—and sometimes outright refusals. They create environments where people are present for presence’s sake, where ideas are shared with no paywall, where community growth doesn’t hinge on growth hacking.

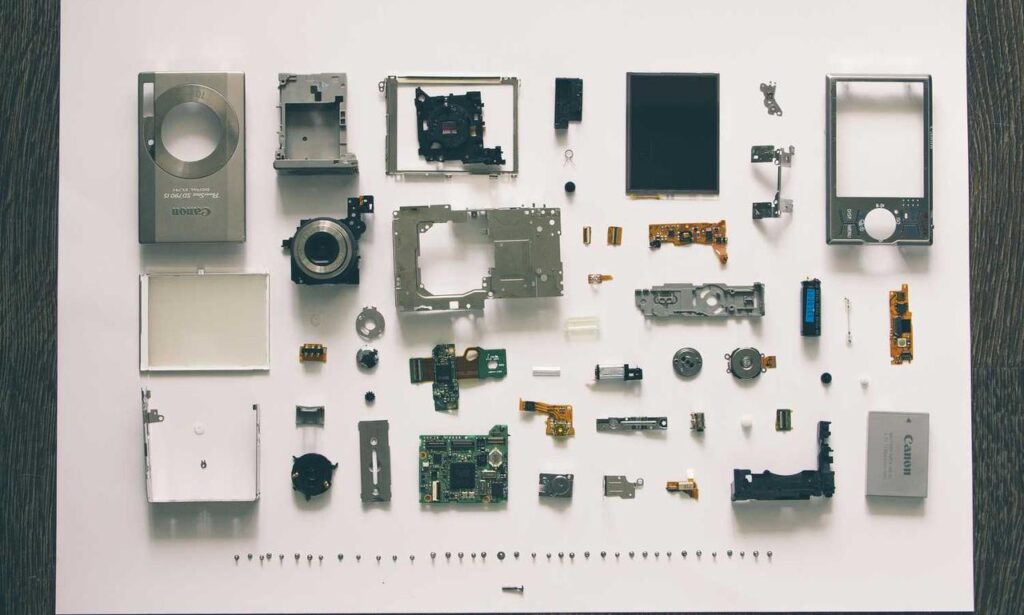

Real-World Examples of Discommercification

Consider community radio stations that run independently, without advertising. Or zines that operate through mutual support rather than glossy sponsorship. These aren’t throwbacks to a pre-digital age—they’re modern, thoughtful designs for media sovereignty.

In the music world, the discommercified spirit lives in DIY shows held in basements and living rooms, where artists perform without middlemen. Even digital projects like open-source software or independent media blogs often embrace discommercified principles—operating on donations or staying ad-free—not out of elitism, but from a commitment to autonomy.

What these examples share is a controlled pace and intentional reach. They’re sustainable not because they’re optimized for profit, but because they prioritize integrity, connection, and sometimes, the right to be small and unscalable.

Challenges in Staying Discommercified

Of course, choosing discommercification isn’t easy. We still live in a world governed by rent, bills, and—yes—money. It’s one thing to say no to commercial interference; it’s another to build systems that support this refusal sustainably.

Crowdfunding is one middle ground many adopt, but even that comes with pressures of deliverables and audience cultivation. Platforms like Patreon may empower creators, but they also operate within capitalist dynamics. Similarly, even when projects start independent, attention often courts monetization, intentionally or not.

Staying discommercified calls for continuous self-awareness. Who benefits from this platform? What are we compromising? Can we fulfill our goals without selling access or influence?

It doesn’t mean cutting off all dealings with money. Instead, it’s about placing commercial logic in its appropriate place—outside the creative, intellectual, emotional, and community cores of a project.

The Broader Why

Why does this matter? Because when everything is up for sale, not much is left that’s sacred. When every thought is filtered through profitability, our most honest, weird, fragile initiatives get diluted or silenced. We narrow the bandwidth for experiment and vulnerability.

Discommercified approaches protect what can’t be priced—spontaneity, cultural memory, raw emotion, and even failure. They’re not about asceticism or nostalgia; they’re about selecting different metrics for success.

They remind us that change doesn’t always look like explosive growth or mass engagement. Sometimes it looks like a room of ten people, gathered not to sell or buy, but to connect, learn, or make something that matters—just because.

A Viable Alternative or Just a Mood?

Skeptics might view discommercification as a passing aesthetic, a vibe for those disillusioned with hustle culture. But growing global networks of activist pods, mutual aid groups, and creative collectives suggest otherwise. There’s a deeper hunger for genuine exchange—rooted in trust rather than commerce.

To be discommercified isn’t to check out of the economy entirely. It’s to ask where commerce belongs—then politely show it the door when the answer is “not here.”

More people are asking those questions. More platforms and projects are experimenting with these answers. Whether they succeed long-term remains to be seen—but they’re building reference points. And for many, that shift in posture is already a win.

Final Thoughts

Reclaiming space from commerce isn’t new. But framing it explicitly—as the discommercified way of doing things—gives language to something quietly powerful. It lets people name the friction they’ve felt when an idea gets co-opted, when the vibe gets sold, when a scene goes from community to commodity.

It’s a small word, but a big direction. And it’s one that’s starting to feel less radical, more practical. Maybe even overdue.